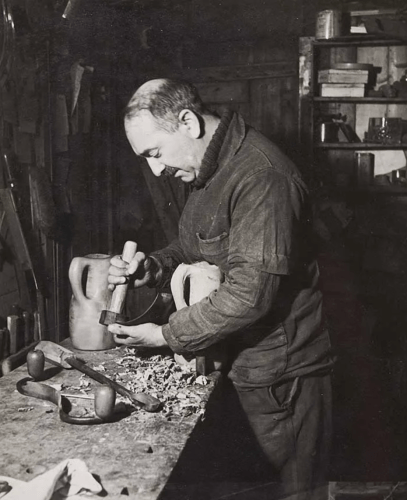

ALEXANDRE NOLL (1890-1970)

Born to Alsatian parents, Alexandre Noll only really turned towards art in the 1920s. During the First World War, however, he made numerous watercolour sketches and more importantly, perhaps, a large number of wood engravings. At the end of the war he decided to develop this technique, which was gradually taken over by sculpture. This began with the creation of parasol handles and evolved into lampstands commissioned by the fashion designer Paul Poiret.

In 1925 Noll exhibited a series of sculpted objects at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes and in 1927 he began to exhibit at the Crémaillère, a gallery devoted to discovering new talent.

It was only, however, in 1935 that Alexandre Noll began to create his ‘furniture sculptures’ that were usually carved into blocks of one specific wood, primarily sycamore, mahogany, teak, or (and in fact most often) ebony. He participated in the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques in a discrete way, but it was only at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in 1939 and at the VIIth Triannale in Milan in 1940 that he exhibited a few small wooden sculptures. It was during the Second World War that Noll began to develop his ideas concerning furniture design and sculpture, and this was when he really started to forge his own style. After the war, in the context of increasing mass-production, he began to produce pieces of wooden furniture that were pure, authentic and, what is more, unique. It was at this point, in the 1950s, that Noll chose to turn definitely towards sculpture. This was, perhaps, a natural evolution. Noll then participated in numerous exhibitions in France, including ‘De la Sculpture de Rodin à nos jours’ and ‘Aux Arts de la table’ at the Pavillion de Marsan (he was notably involved in Jacques Adnet’s stand), and in others abroad, in Munich, Madrid, Vienna, London, Varèse etc.

Alexandre Noll did not just work with wood; his approach and technique were both intimately bound up with nature and purity of form in a way that was simultaneously poetic, intuitive and philosophical.